Sir Francis Glanville, Kt., M.P., J.P., and Deputy Lieutenant for the County of Devon, of Kilworthy, near Tavistock,

Was the eldest son of Judge Glanville. The earlier days of Francis were spent in

vicious living and great profligacy in. London. His father had often threatened to disinherit

him if he did not amend his ways and choose a better calling in life ; but Francis,

not heeding these threats, and probably thinking that his father would not be so

unnatural as to cut him out of his will, continued these wild pranks until one day he

happened, in a singular manner, to save the life of William Crymes, Esq., a landowner in

Devon, from the hands of a band of assassins in the streets of London. Mr Crymes, not

knowing who the preserver of his life was, asked Francis to call at his house in London

the day after the attempted outrage, so that he could then more fully express his deep

gratitude to his preserver.

Next day, at the appointed hour, Francis waited upon Mr. Crymes as he had been

invited to do. When the hall door was opened Francis inquired for the gentleman of the

house, but being informed by the old retainer of the Crymes's that his master was then

engaged, he asked him to sit down and wait until he was able to see him. While Francis

was waiting to be called into the presence of Mr. Crymes, his eye caught the beautiful

portrait of Elizabeth Crymes, the young daughter, hanging on the wall. The first sight

of this lovely face struck deeply into the heart of Master Frank Glanville, and from that

moment he made up his mind to marry the original of the picture, which, as will be shortly

seen, he did do. Having waited some time, he was at last ushered into the presence of the

gentleman whose life he had so nobly preserved, and after the most grateful acknowledgments

on the part of Mr. Crymes, he proceeded to inquire the name of his preserver,

whereupon Francis informed him that he was the eldest son of Sir John Glanville, who

lived at Tavistock in Devonshire. Imagine the surprise of Frank when Mr. Crymes told

him that he also lived in Devonshire; and not only that, but likewise resided near

Tavistock, and was intimately acquainted with his father, the Judge. The question next

arose, what should Mr. Crymes do for Francis in recognition for his timely protection.

Francis replied that he much desired Mr. Crymes to intercede between his father and

himself. This Mr. Crymes gladly promised to do directly on his return into Devon.

The mission of peace no doubt would have been successful had not death taken Judge

Glanville, for on the arrival of Mr. Crymes at Kilworthy he found that Francis's father had

gone to his last home, and that his younger brother, John Glanville, had succeeded to the

property which really belonged by right of birth to Francis. This sad event led Frank to

moralize on the follies of his youth, and ended by his making up his mind to cut all his

old friends and entirely amend his present living. Having come to this laudable

determination, Francis set to with a hearty goodwill to make up for lost time. Entering

himself as a law student, he rapidly regained the good opinions of his relations, and

among the first to recognise his improvement was his own brother. Sir John Glanville,

which he did in a right noble manner, as I shall now relate. When Sir John was fully

convinced of his brother Francis's penitence, he sent and invited him to a feast that he

proposed giving to his friends at Kilworthy. When the repast was nearly finished one

dish was ordered by Sir John to be placed before Francis, which being done, he bade him

lift the cover and accept the contents. Francis obeyed, and much to his astonishment,

as well as to that of the company present, instead of finding savoury meats, the dish

contained a bundle of writings, whereupon Sir John Glanville informed the company

that what he now did was only the same act that he felt assured would have been performed

by his father could he have lived to witness the happy change which they

all knew had taken place in his eldest son; therefore he freely restored to his brother

the whole estates. Francis proved worthy of the trust his brother had reposed in

him, for he lived to be knighted and to perform many useful acts of service to his

country. [fn 118]

In 1620 Sir Francis Glanville and Sir Baptist Hexte were elected Members of

Parliament for Tavistock. In 1625 he again sat for the same town with John Pym, Esq.,

and also in 1628. The Rectory of Charlton Musgrove becoming vacant in 1617, Glanville,

as patron, presented the Rev. Richard Leir, B.D., of Exeter, aa Rector.

King James, in his letter written from Theobalds, and dated the 11th December,

1623, to Lord Keeper Lincoln, renewed Lord Russel's commission of Lieutenancy for

Devonshire and Exeter, and added to the list of Deputy Lieutenants Sir Francis Glanville

and Lewis Pollard for Devonshire, and Jeffry Waltham and John Modeford for Exeter.

In the year 1626, February 27th, Sir Francis Glanville wrote from Tavistock to

Secretary Conway on behalf of his brother, William Crymes, and requested Lord Conway

to give some good words to the Master of the Wards for obtaining the Wardship of his

son. Sir Francis also recommended another person who was summoned to appear before the

Privy Council. Sir Francis likewise held the position of a Magistrate in his native

county, for Francis, Earl of Bedford, writing to the Privy Council in 1638, informed the

Lords that he had examined the Account of William Hockin, son and executor of

Christopher Hockin, for conduct money received by the said C. Hockin from the N.

division of Devonshire in 1627, and sums thereout expended for billeting soldiers who

had returned from Rhe. The Earl added that the King sent down money on behalf of the

county, out of which Mr. Hockin, instead of £300, received only £96 7s. 9d which he

paid out according to a warrant signed by Baronet Chudleigh, Sir William Stroud, and

Sir Francis Glanville.

In 1635 the Harbour of Catwater, Devon, had become out of repair, so much

so that the Mayor and Commonalty of Plymouth were obliged to petition the Lords of

the Privy Council, Sir Francis Glanville, Sir James Bagg, Sir Nicholas Slanning, and

others, certifying to the "great decays" of the said harbour. The matter was referred

to the Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench and Common Pleas, and the Lord Chief

Baron, to consider the best ways and means for raising money to repair the harbour.

Again on the 26th April, 1636, Thomas Crampporne, Mayor of Plymouth, Sir James Bagg,

and Sir Francis Glanville addressed the Privy Council, and informed the Lords that

they, according to their order of the 5th of February last, had viewed the harbour of

Catwater, near Plymouth, which they found much decayed, and "quar'd" up, which

they attributed to the quantities of sand and earth thrown out of certain tin-works,

and ballast cast out at Saltash, and also allowing a ship sunk there eleven years

since to lie still, and to the quantities of sand and gravel brought down by the rivers

Plym and Mew.

Sir Francis Glanville married Elizabeth, daughter of William Crymes of Buckland Monachorum, Devon, Esq., on 21st September, 1604 (she was the lady whose portrait had so much struck Francis when he was awaiting his interview with Mr. Crymes,

her father), and by her had issue:-

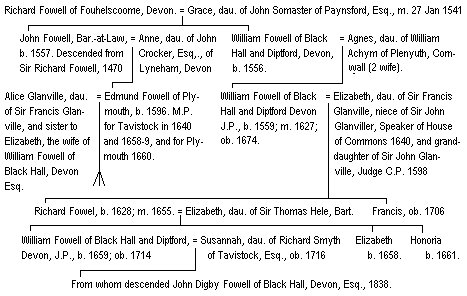

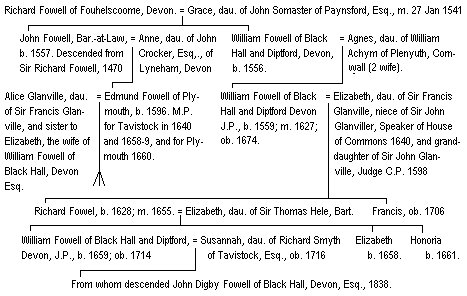

1. John Glanville of Kilworthy, Esq., died before 1620 without issue.

2. Alice Glanville, married Edmund Fowell (son of John Fowell, Esq., Barrister-

at-Law), M.P. for Tavistock in the years 1640, 1658, and 1659, and again in 1660 for

Plymouth. He was a frequent speaker in the House. Edmund Fowell married secondly

Jane, daughter of Sir Anthony Barker of Sunning in Berkshire.

3. Elizabeth Glanville, married William Fowell of Black Hall and Diptford,

Devon, Esq., a representative of one of the finest old Devonshire houses.

4. Dionysia Glanville, married 1635 John Doidge of Harlesditch and Willow

Street, Devon, Esq. The Doidge family rank amongst the oldest and most respectable

of freeholders of Devon. The eldest son of this union, John Doidge, was M.P. for

Tavistock, and High Sheriff of Devonshire. He married Judith, daughter of Sir Nicholas

Trevanion, and had one daughter, Maria, his heiress, who allied herself to the Reverend

William Taunton of Freeland Lodge, Oxford, whose son, Joseph Taunton of Totness,

married Margaret, daughter of B. Babbage, and their son, William Doidge Taunton

(born 1781), became Mayor of Totness.

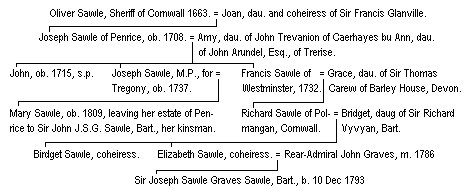

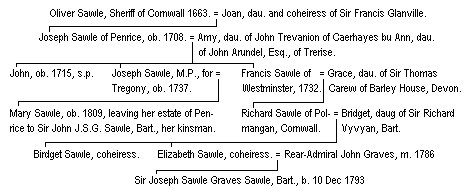

5. Joan Glanville, married in 1632 Oliver Sawle of Penrice, Cornwall, Esq., who

in 1663 was Sheriff of Cornwall; from this alliance descended the present Baronet, as the

following pedigree will shew:-

6. Francis Glanville, who succeedecl his father. Sir Francis Glanville, in the Kilworthy

property, married, 11th March 1647, Maria Bolle, [fn 1190 daughter of Henry Rolle of

Heanton, Devon, Esq. Dying without isssue he left his property to his sister, Margaret

Glanville, who became the wife of William Kelly of Kelly, Devon, Esq., and she brought

with her into that family the Kilworthy property, which descended to her only daughter,

Elizabeth Kelly of Kelly and Kilworthy, who married Ambrose Manaton of Trecaral, Esq.

(son of Ambrose Manaton, by Ann, daughter of P. Edgecumbe of Edgecumbe, Esq.), and

into the Manaton family passed the Glanville property.

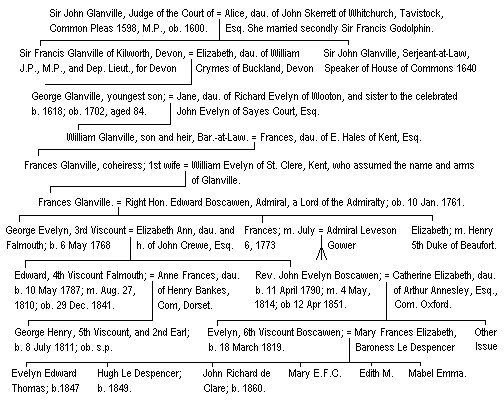

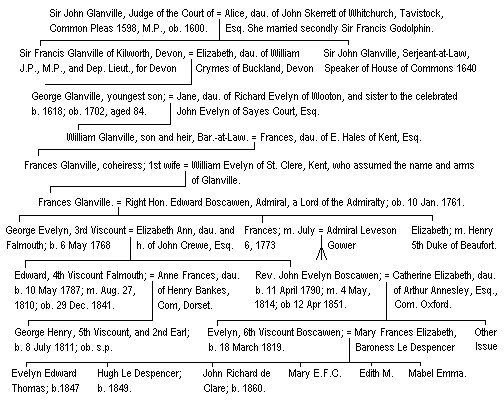

7. George Glanville, youngest brother to the preceding, was born in 1618, and

married Jane, daughter of Richard Evelyn of Wooton, Surrey, and sister to the celebrated

John Evelyn of Sayes Court. Evelyn, in his 'Diary' says, "June 1st, 1691, I went

with my son and brother-in-law Glanvill and his son to Wooton to solemnize the funeral

of my nephew (Glanville), which was performed the next day, very decently and orderly

by the Heralds, in the afternoon, a very great appearance of the country being there."

On the death of George Glanville, Evelyn also writes, "1702, April 12th, my brother-in-law

Glanville departed this life this morning, after a long languishing illnesse, leaving a

son by my sister, and two granddaughters. Our relation and friendship had been long

and greate. He was a man of excellent parts. He died in the 84th year of his age, and

will'd his body to be wrapped in lead and carried down to Greenwich, put on board a

ship, and buried in the sea about Dover and Calais, about the Goodwin Sands, which was

done on the Tuesday or Wednesday after. He was a gentleman of an ancient family in

Devonshire, and married my sister Jane. By his prudent parsimony he much improved his

fortune. He had a place in the Alienation Office, and might have made an extraordinary man

had he cultivated his parts" George Glanville, as Evelyn says, left issue one son, William

Glanville, Barrister-at-Law, who married Frances, daughter of E. Hales of Kent,Esq., [fn 120] and

by her had two daughters - Francis Glanville, who became eventually heiressto her father on

her sister's death, married her cousin William Evelyn of St. Clere, in Kent, [fn 121] who assumed

the name and arms of "Glanville," and had issue a daughter:-

Frances Glanville, who became the wife of the Honourable Edward Boscawen,

Admiral of the Blue, General of Marines and a Lord of the Admiralty. This distinguished

officer was the second son of Hugh Boscawen, Viscount Falmouth, by his wife

(married 23rd April, 1700), Charlotte, elder daughter and coheiress of Charles Godfrey,

Esq., and niece maternally of the celebrated Duke of Marlborough. By the union of

Admiral Boscawen with Frances Glanville, three children survived:-

1. George Evelyn, b. 6th May, 1758, and who became third Viscount Falmouth.

2. Frances, married 6th July, 1773, Admiral John Leveson Gower, brother to

Granville, first Marquis of Stafford.

3. Elizabeth, married Henry, fifth Duke of Beaufort.

Pedigree shewing the Descent of the present Viscount Falmouth from the Glanvilles.

Sir John Glanville of Broadhinton Manor, Wilts, Speaker of the House of Commons 1640, D.C.L., and Serjeant-at-Law to Charles I. and II

SIR JOHN GLANVILLE, a younger son of Judge Glanville, and brother to Sir Francis, was

born at Kilworthy, near Tavistock, about 1589. By his father's will he inherited Kilworthy,

but, as already shewn, he nobly returned that estate to his elder brother. Sir

John Glanville at an early age entered himself as a student at Lincoln's Inn, and with

the help of his father's notes he soon rose in his profession, and practised as a councillor

with great reputation. In the year 1614, he was elected Recorder of Plymouth, and

Member of Parliament, in company with Thomas Sherwill, Esq., for the same town, and

was again elected for that place in the years 1620, 1623, 1625, 1626, and 1628. In the

Parliament that met Feb. 6, 1620, Mr. Glanville spoke on the decrease of money, and said

"That there is a great complaint throughout the kingdom of .the great scarcity of money,

which is a business worthy the consideration of this House. 1, Whether there be such

want of money or not; 2, What are the causes of it? For the first, he believeth that

there is a want and scarcity of coin, because of the general complaint of all men; for that

landlords can get no rent of their farmers; for that the price of land is fallen from twenty

years' purchase to eighteen, sixteen, fourteen, and in some places to thirteen and twelve

years' purchase; and for that the Mint for coinage hath not gone these ten or twelve

years. Second, that the reasons and causes of the want of money are divers - more than,

he doubteth, can be found out, or will be revealed; some say there is too much coin carried

northward; that our expenses and cost on foreign commodities and merchandise is another

cause; and the excess of plate, insomuch that gentlemen of ordinary fashion will be served

in plate; and although this may be thought a means to treasure up silver and gold against

a time of scarcity and need, yet is there great want of it by using it. The patent of the

East India Company's another cause of the want of money, for though they affirm they

carry away, they carry no plate or coin out of this kingdom, but that they have it elsewhere;

yet they sell our commodities beyond sea, and from thence carry the money they

receive from them into the East Indies, and so forestall the coming of the money hither."

The position of England previous to the meeting of the third Parliament of King

Charles I. was serious in the extreme; there was every reason to apprehend disorder or an

insurrection from the discontented portion of the English people. The nation had met with

disasters during the Spanish war, and the French campaign had nearly annihilated its

commerce; but not only these misfortunes raised the indignation of a proud race, but

also a really more important and sacred right was, they thought, being gradually taken

from them their liberties, which their forefathers had spent so much blood to obtain,

were now in the balance; and King Charles was blamed for admitting into his councils

the ambitious Duke of Buckingham. When the King perceived that it was absolutely

necessary to summon the estates of the realm, both he and the Duke dreaded the consequences,

although the latter pretended that it had been through his advice the King

had called Parliament together. On the 17th March, 1628, the Commons of England

assembled, and the majority of them seemed to be men of the same high and independent

spirit that animated their ancestors; and their property was computed to be three times

as great as that of the Upper House.

In Charles's first speech he told the Commons that "He must, in discharge of his

conscience, use those other means which God had put into his hands in order to save that

which the follies of some particular men may otherwise put in danger;" this of course alluded

to Parliamentary supplies. From the above speech the Commons foresaw that, on the least

pretence, the King would dissolve them, which if that happened, either insurrection or,

worse still, a civil war would break out. The feelings of the people compelled Parliament

to pass a vote against arbitrary imprisonments and forced loans. Charles now applied

for money, and five subsidies had been already voted him, but although voted, they had not

passed into law; and before it did so, the Commons resolved to employ the interval in

devising some measures to protect their rights and liberties which had been so lately

violated, and for this purpose they appointed a committee, which drew up the celebrated

PETITION OF RIGHT, and Mr. Recorder Glanville and Sir Henry Martin were intrusted with

its passage through the House of Lords.

On the 23rd May, 1628, Glanville delivered the following speech in a full committee

of both Houses of Parliament, in the Painted Chamber at Westminster, on the liberty of

the subject:-

My Lords, I have in charge from the Commons' House of Parliament (whereof I am a

member) to express this day before your lordships some part of their clear sense, touching one point that

hath occurred in the great debate which hath so long depended in both Houses. I shall not need many

words to induce or state the question which I am to handle in this free conference. The subject matter

of our meeting is well known to your lordships, I will therefore only look so far back upon

it, and so far recollect summarily the proceedings it hath had, as may be requisite to present clearly

to your lordships' consideration the nature and consequence of the particular wherein I must insist.

Your lordships may be pleased to remember now that the Commons in this Parliament

have framed a petition to be presented, to his Majesty; a Petition of Right, rightly composed, relating

nothing but truth, desiring nothing but justice; a petition justly occasioned; a petition necessary

and fit for these times; a petition founded upon solid and substantial grounds, the laws and statutes of

this realm - sure rocks to build upon; a petition bounded within due limits, and directed upon

right ends, to vindicate some lawful and just liberties of the free subjects of this kingdom from the

prejudice of violations past, and to secure them from future innovations; and because my following

discourse must reflect chiefly, if not wholly, upon the matter of this Petition of Right, I shall here

crave leave shortly to open to your lordahips the distinct parts whereof it doth consist, and those

are four. The first concerns levies of moneys, by way of loans or otherwise, for his Majesty's supply:

declaring that no man ought, and praying that no man hereafter be compelled, tomake or yield any

gift, loan, benevolence, tax, or such like charge without common consent by Act of Parliament. The

second is concerning that liberty of person which rightfully belongs to the free subjects of this realm,

expressing it to be against the tenure of the laws and statutes of the land that any freeman should

be imprisoned without cause shewn; and then reciting how this liberty, amongst others, hath lately

been infringed, it concludeth with a just and necessary desire for the better clearing and allowance

of this privilege for the future. The third declareth the unlawfulness of billeting or placing

soldiers or mariners to sojourn in free subjects' houses against their wills, and prayeth remedy against

that grievance. The fourth and last aimeth at redress touching commissions to proceed to the trial

and condemnation of offenders, and causing them to be executed and put to death by the law martial,

in times and places, when and where, if by the laws and statutes of the land they have deserved death

by the same laws and statutes also they might, and by none other ought to be adjudged and executed.

This petition the careful House of Commons, not willing to omit anything pertaining to

their duties, or which might advance their moderate and just ends, did therefore offer up unto

your lordships' consideration, accompanied with an humble desire that in your nobleness and

justice you would be pleased to join with them in presenting to his Majesty, that so coming from

the whole body of this realm, the Peers and People, to him that is the head of both, our gracious

sovereign, who must crown the work, or else all our labour is in vain, it might, by your lordships'

concurrence and assistance, find the more easy passage, and obtain the better answer.

Your lordships, as your manner is in cases of so great importance, were pleased to debate

and weigh it well, and thereupon yon propounded to us some new amendments (as you termed

them) by way of alteration, alleging that they were only in matters of form, and not of substance;

and that they were intended to no other end but to sweeten the petition and make it the most

passable with his Majesty.

In this the House of Commons cannot but observe that fair and good respect which your

lordships have used in your proceedings with them by your concluding or voting nothing in your

House until you had imparted it unto them, whereby our meetings about this business have been

justly styled free conferences, either party repairing hither disengaged, to hear and weigh the

other's reasons, and both Houses coming with a full intention, upon due consideration of all that can

be said on the other side, to join at last in resolving and acting that which shall be found most just

and necessary for the honour and safety of his Majesty and the whole kingdom. And touching

those propounded alterations, which were not many, your Lordships cannot but remember that the

House of Commons have yielded to an accommodation, or change of their petition in two particulars;

whereby they hope your lordships have observed, as well as you may, they have not been

affected unto words and phrases, not overmuch abounding in their own sense, but rather willing to

comply with your lordships in all indifferent things. For the rest of your proposed amendments, if

we do not misconceive your lordships, as we are confident we do not, your lordships of yourselves

have been pleased to relinquish them, with a new overture for one only clause to be added in the

end or foot of the petition, whereby the work of this day is reduced to one simple head, whether

that clause shall be received or not. This yielding of the Commons in part unto your lordships,

on other points by you somewhat insisted upon, giveth us great assurance that our ends are one;

and putteth us in hope that in conclusion we shall concur and proceed unanimously to seek the

same means.

The clause propounded by your lordships to be added to the petition is this:-

"We humbly, present this Petition to your Majesty not only with a care for preservation

of liberties, but with a due regard to leave entire that sovereign power wherewith your Majesty is

intrusted for the protection, safety, and happiness of your people." A clause specious in shew and

smooth in words, but in effect and consequence most dangerous, as I hope to make most evident.

However, coming from your lordships, the House of Commons took it into their considerations,

as became them, and apprehending upon the first debate that it threatened ruin to the whole

petition, they did heretofore deliver some reasons to your lordships for which they then desired

to be spared from admitting it.

To these reasons, your lordships offered some answers at the last meeting; which having

been faithfully reported to our House, and there debated as was requisite for a business of such

weight and importance, I must say truly to your lordships, yet with due reverence to your opinions,

the Commons are not satisfied with your arguments; and therefore they have commanded me to

recollect your lordships' reasons for this clause, and in a fair reply to let you see the causes why

they differ from you in opinion.

But before I come to handle the particulars wherein we dissent from your lordships, I

will in the first place take notice yet a little farther of that general wherein we all concur; which

is, that we desire not, neither do your lordships, to augment or dilate the liberties and privileges

of the subjects beyond the just and due bounds, nor to encroach upon the limits of his Majesty's

prerogative royal. And as in this, your lordships at the last meeting expressed clearly your own

senses, so were your lordships not mistaken in collecting the concurrent sense and meaning of the

House of Commons; they often have protested, they do, and ever must protest, That these have

been, and shall be the bounds of their desires, to demand and seek nothing but that which may be

fit for dutiful and loyal subjects to ask, and for a gracious and just king to grant; for as they claim

by laws some liberties for themselves, so do they acknowledge a prerogative, a high and just prerogative

belonging to the king, which they intend not to diminish. And now, my lords, being

assured, not by strained inferences or obscure collections, but by the express and clear declarations

of both Houses, that our ends are the same, it were a miserable unhappiness if we should fail in

finding out the means to accomplish our desires.

My lords, the heads of those particular reasons which you insisted upon the last day

were only these:

1. You told us that the word "leave" was of such a nature that it could give no new

thing to his Majesty.

2. That no just exception could be taken to the words "sovereign power;" for that as

his Majesty is a King, so he is a sovereign; and as he is a sovereign, so he hath power.

3. That the sovereign power mentioned in this clause is not absolute or indefinite, but

limited and regulated by the particle "that;" and the word "subsequent" which restrains it to

be applied only for protection, safety, and happiness of the people, whereby ye inferred there

could be no danger in the allowance of such power.

4. That this clause contained no more in substance, but the like expressions of our meanings

in this petition, which we had formerly signified unto his Majesty by the mouth of Mr. Speaker,

that we no way intended to encroach upon his Majesty's sovereign power or prerogative.

5. That in our petition we have used other words, and of larger extent, touching our

liberties, than are contained in the statutes whereon it is grounded: In respect of which enlargement,

it was fit to have some express, or implied saving, or narrative declaratory for the king's

sovereign power, of which narrative you allege this clause to be.

Lastly. Whereas the Commons, as a main argument against, the clause, had much insisted

upon this, that it was unprecedented and unparliamentary in a petition from the subject to insert

a saving for the crown; your lordships brought for instance to the contrary, the two statutes of

the 25 Ed. I commonly called confirmatio chartarum, and 26 Ed. I., known by this name Articuli

super Chartas; in both which statutes there are savings for the king.

Having thus reduced to your lordships' memories the effects of your own reasons, I will

now, with your lordships' favour, come to the points of our reply, wherein I must humbly beseech

your lordships to weigh the reasons which I shall present, not as the sense of myself, the weakest

member of our House, but as the genuine and true sense of the whole House of Commons, conceived

in a business there debated with the greatest gravity and solemnity, with the greatest concurrence

of opinions, and unanimity, that ever was in any business maturely agitated in that House.

I shall not, peradventure, follow the method of your lordships' recollected reasons in my answering

to them, nor labour to urge many reasons. It is the desire of the Commons that the weight of

their arguments should recompense, if need be, the smallness of their number. And, in conclusion,

when you have heard me through, I hope your lordships shall be enabled to collect clearly, out of

the frame of what I shall deliver, that in some part or other of my discourse there is a full and

satisfactory answer given to every particular reason or objection of your lordships.

The reasons that are now appointed, to be presented to your lordships are of two kinds,

legal and rational, of which those of the former sort are allotted, to my charge; and the first of

them is thus:-

The clause now under question, if it be added to the petition, then either it must refer

or relate unto it, or else not; if it have no such reference, is it not clear that it is needless and

superfluous? And if it have such reference, is it not clear that then it must needs have an

operation upon the whole petition and upon all the parts of it? We cannot think that your lordships

would offer us a vain thing; and therefore taking it for granted, that if it be added, it would

refer to the petition; let me beseech your lordships to observe with me, and with the House of

Commons, what alteration and qualification of the same it will introduce.

The petition of itself, simply, and without this clause, declareth absolutely the rights and

privileges of the subject, in divers points; and among the rest touching the levies of moneys, by

way of loans or otherwise, for his Majesty's supply, That such loans and other charges of the like

nature, by the laws and statutes of this land, ought not to be made or laid without common consent

by Act of Parliament: But admit this clause to be annexed with reference (to the petition), and it

must necessarily conclude and have this exposition, That Loans and the like charges (true it is,

ordinarily) are against the laws and statutes of the realm, "unless they be warranted by sovereign

power," and that they cannot be commanded or raised without assent of Parliament, "unless it be

by sovereign power:" What were this but to admit a sovereign power in the king above the laws

and statutes of the kingdom?

Another part of this petition is, That the free subjects of this realm ought not to be

imprisoned without cause shewed: But by this clause a sovereign power will be admitted, and left

entire to his Majesty, sufficient to control the force of law, and to bring in this new and dangerous

interpretation, That the free subjects of this realm ought not by law to be imprisoned without cause

shewed, "unless it be by sovereign power."

In a word, this clause, if it should be admitted, would take away the effect of every part of

the petition, and become destructive to the whole: for thence will be the exposition touching the

billeting of soldiers and mariners in freemen's houses against their wills; and thence will be the

exposition touching the times and places for execution of the law martial, contrary to the laws

and statutes of the realm.

The scope of this petition, as I have before observed, is not to amend, our case, but to

restore us to the same state we were in before; whereas, if this clause be received, instead of

mending the condition of the poor subjects, whose liberties of late have been miserably violated by

some ministers, we shall leave them worse than we found them; instead of curing their wounds, we

shall make them deeper. We have set bounds to our desires in this great business, whereof one is

not to diminish the prerogative of the king, by mounting it too high; and. if we bound ourselves on

the other side with this limit, not to abridge the lawful privileges of the subject, by descending

beneath that which is meet, no man, we hope, can blame us.

My lords, as there is mention made in the additional clause of sovereign power, so is there

likewise of a trust reposed in his Majesty, touching the use of sovereign power.

The word "Trust" is of great latitude and large extent, and therefore ought to be well and

warily applied and restrained, especially in the case of a king: there is a trust inseparably reposed

in the persons of the kings of England, but that trust is regulated by law. For example, when

statutes are made to prohibit things not mala in se, but only mala quia prohibita, under certain

forfeitures, and penalties, to accrue to the king, and to the informers that shall sue for the breach

of them; the Commons must and ever will acknowledge a regal and sovereign prerogative in the

king, touching such statutes, that it is in his Majesty's absolute and undoubted power to grant

dispensations to particular persons, with the clauses of non obstante, to do as they might have done

before those statutes, wherein his Majesty, conferring grace and favour upon some, doth not do

wrong to others. But there is a difference between those statutes, and the laws and statutes

whereupon the petition is grounded: by those statutes the subject has no interest in the penalties,

which are all the fruit such statutes can produce, until by suit or information commenced he

become entitled to the particular forfeitures; whereas the laws and statutes mentioned in our

petition are of another nature; there shall your lordships find us rely upon the good old statute,

called Magna Charta, which declareth and confirmeth the ancient common laws of the liberties of

England: there shall your lordships also find us to insist upon divers other most material statutes,

made in the time of Kings Edw. III. and Edw. IV., and other famous kings, for explanation and

ratification of the lawful rights and privileges belonging to the subjects of this realm: laws not

inflicting penalties upon offenders, in malis prohibitis, but laws declarative or positive, conferring

or confirming, ipso facto, an inherent right and interest of liberty and freedom in the subjects of

this realm, as their birthrights and inheritance descendable to their heirs and posterity;

statutes incorporate into the body of the common law, over which (with reverence be it spoken)

there is no trust reposed in the king's "sovereign power," or "prerogative royal," to enable him to

dispense with them, or to take from his subjects that birthright or inheritance which they have in

their liberties, by virtue of the common law and of these statutes.

But if this clause be added to our petition, we shall then make a dangerous overture to

confound this good destination touching what statutes the king ia trusted to control by dispensations,

and what not; and shall give an intimation to posterity, as if it were the opinion both of the

Lords and Commons assembled in this Parliament, that there is a trust reposed in the king, to lay

aside by his "sovereign power," in some emergent cases, as well the Common-Law, and such

statutes as declare or ratify the subjects' liberty, or Confer interest upon their persons, as those

other penal statutes of such nature as I have mentioned before; which, as we can by no means

admit, so we believe assuredly, that it is far from the desire of our most gracious sovereign, to

effect so vast a trust, which being transmitted to a successor of a different temper, might enable

him to alter the whole frame and fabric of the commonwealth, and to resolve that government

whereby this kingdom hath flourished for so many years and ages, under his Majesty's most royal

ancestors and predecessors.

Our next reason is, that we hold it contrary to all course of Parliament, and absolutely

repugnant to the very nature of a Petition of Right, consisting of particulars, as ours doth, to clog

it with a general saving or declaration, to the weakening of the right demanded; and we are bold.

to renew with some confidence our allegation, that there can be no precedent shewed of any such

clause in any such petitions in times past.

I shall insist the longer upon this particular, and labour the more carefully to clear it,

because your lordships were pleased the last day to urge against us the statutes of 25 and 28 of

Edw. I. as arguments to prove the contrary, and seemed not to be satisfied with that which in this

point we had affirmed. True it is, that in those statutes there are such savings as your lordships

have observed; but I shall offer you a clear answer to them, and to all other savings of like nature

that can be found in any statutes whatsoever.

First in the general, and then I shall apply particular answers to the particulars of those

two statutes; whereby it will be most evident that those examples can no ways suit with the

matter now in hand. To this end it will be necessary that we consider duly what that question is,

which indeed concerneth a petition, and not an Act of Parliament. This being well observed, by

shewing unto your lordships the difference between a petition for the law, and the law ordained

upon such a petition, and opening truly and perspicuously the course that was holden in framing

of statues before 2 Hen. V., different from that which ever since then hath been used, and is still

in use amongst us, and by noting the times wherein these statutes were made, which was about one

hundred years before 2 Hen. V., besides the differences between these savings and this clause; I

doubt not but I shall give ample satisfaction to your lordships, that the Commons, as well in this as

in all their other reasons, have been most careful to rely upon nothing but that which is most true

and pertinent.

Before the second year of King Henry V. the course was thus: when the Commons were

suitors for a law, either the Speaker of their House by word of mouth from them, the lords' house

joining with them, or by some Bill in writing, which was usually called their Petition, moved the

king to ordain laws for the redress of such mischiefs or inconveniences as were found grievous

unto the people.

To these petitions the king made answer as he pleased, sometimes to part, sometimes to the

whole, sometimes by denial, sometimes by assent, sometimes absolutely, and sometimes by qualification.

Upon these motions and petitions, and the king's answers to them, was the law drawn, up

and ingrossed in the statute-roll to bind the kingdom; but this inconvenience was found in this

course, that oftentimes the statutes thus framed were against the sense and meaning of the

Commons, at whose desires they were ordained; and therefore in the 2 Hen. V finding that it

tended to the violation of their liberty and freedom, whose right it was, and ever had been, that no

law should be made without their assent, they then exhibited a petition to the king, declaring their

right in this particular: praying, that from thenceforth no law might be made or ingrossed as

statutes) by additions or diminutions to their motions or petitions, that should change their sense

or intent, without their assent; which was accordingly established by Act of Parliament. Ever

since then the right hath been) as the use was before, that the king taketh the whole, or leaveth the

whole of all Bills or Petitions) exhibited for the obtaining of laws.

From this course, and from the time when first it became constant and settled, we conclude

strongly, that it is no good argument, because ye find savings in Acts of Parliaments before the

second of Hen. V., that those savings were before in the petitions that begat those statutes: for if

the petitions for the two loans so much insisted upon, which petitions, for any thing we know, are

not now extant, were never so absolute, yet might the king, according to the usage of those times,

insert the savings in his answers; which passing from thence into the statute-roll, do only give

some little colour, but are not proof at all that the petitions also were with savings.

This much for the general: to come now to the particular statute of 25 Edw. I., which was

a confirmation of Magna Charta, with some provision for the better execution of it, as Common

law, which words are worth the noting. It is true, that statute hath also a clause to this effect,

That the king, or his heirs, from thenceforth shall take no aids, taxes, or prisage of his subjects,

but by common assent of all the realm, saving the ancient aids and prisage due and accustomed.

This saving, if it were granted (which is not, nor cannot be proved) that it was as well in

the petition as in the Act; yet can it no way imply that it is either fit or safe that the clause now

in question should be added to our petition: for the nature and office of a saving, or exception, is

to exempt particulars out of a general, and to ratify the rule in things not exempted, but in no sort

to weaken or destroy the general rule itself.

The body of that law was against all aids, and taxes, and prisage in general, and was a

confirmation of the common law, formerly declared by Magna Charta; the saving was only of aids

and prisage in particular, so well described and restrained by the words, "ancient and accustomed,"

that there could be no doubt what could be the clear meaning and extent of that exception; for

the king's right to those ancient aids, intended by that statute to be saved to him, was well known

in those days, and is not yet forgotten.

These aids were three; from the king's tenants by knight's service, due by the common law,

or general custom of the realm: aid to ransom the king's royal person, if unhappily he should be

taken prisoner in the wars: aid to make the king's eldest son a knight, and aid to marry the king's

eldest daughter once, but no more: and that those were the only aids intended io be saved to the

crown by that statute, appeareth in some clearness by the Charter of King John, dated at Running-Mead

the 15th of June, in the fifth year of his reign, wherein they are enumerated with an

exclusion of all other aids whatsoever. Of this Charter I have here one of the originals, whereon

I beseech your lordships to cast your eyes, and give me leave to read the very words which concern

this point. These words, my lords, are thus: "Nullum scutagium vel auxilium ponatur in regno

nostro, nisi per commune consilium regni nostri, nisi ad corpus nostrum redimendum, et primogenitum

filium nostrum militem faciendum, et ad filiain nostram primogenitam semel mairitandam,

et ad hoc non fiat nisi rationabile auxilium."

Touching prisage, the other thing excepted by this statute, it is also of a particular right to

the crown so well known, that it needeth no description, the king being in possession of it by every

day's usage. It is to take one tun of wine before the mast, and another behind the mast, of every

ship bringing in above twenty tuns of wine, and here discharging them by way of merchandise.

But our petition consisteth altogether in particulars, to which if any general saving, or

words amounting to one, should be annexed, it cannot work to confirm things not excepted, which

are none, but to confound things included, which are all the parts of the petition; and it must

needs beget this dangerous exposition, -that the rights and liberties of the subject, declared and

demanded by this petition, are not theirs absolutely, but sub modo; not to continue always, but

only to take place, when the king is pleased not to exercise that "sovereign power," wherewith, this

clause admitted, he is trusted for the protection, safety, and happiness of his people. And thus

that birthright and inheritance, which we have in our liberties, shall by our own assents be turned

into a mere tenancy at will and sufferance.

Touching the statute of 28 Edw. I., Articuli super Chartas; the scope of that statute, among

other things, being to provide for the better observing and maintaining of Magna Charta, hath in

it nevertheless two savings for the king; the one particular, as I take it, to preserve the ancient

prisage, due and accustomed, as of wines and other goods; the other general, seigniory of the crown

in all things.

To these two savings, besides the former answers, which may be for the most part applied to

this statute as well as to the former, I add these further answers: the first of these two savings is

of the same prisage of wines, which is excepted in the 25 Edw. I., but in some more clearness; for

that here the word, wines, is expressly annexed to the word, prisage, which I take for so much to

be in exposition of the former law: and albeit these words, and of other goods, be added, yet do I

take it to be but a particular saving, or exception, which being qualified with the words, ancient,

due, and accustomed, is not very dangerous, nor can be understood of prisage or levies upon goods of

all sorts at the king's will and pleasure; but only of the old and certain customs upon wool,

woolfels, and leather, which were due to the crown, long before the making of this statute.

For the latter of the two savings in this act, which is of the more unusual nature, and

subject to the more exception; it is indeed general, and if we may believe the concurrent relations

of the Histories of those times, as well those that are now printed, as those that remain only in

manuscripts, it gave distaste from the beginning, and wrought no good effect, but produced such

distempers and troubles in the state, as we wish may be buried in perpetual oblivion; and that the

like saving in these and future times may never breed the like disturbance: for from hence arose a

jealousy, that Magna Charta, which declared the ancient right of the subject, and was an absolute

law in itself, being now confirmed by a latter act, with this addition of a general saving; for the

king's right in all things by the saving was weakened, and that made doubtful, which was clear

before. But not to depart from our main ground, which is, that savings in old Acts of Parliament,

before the 2 H. V., are no proof that there were the like savings in the petitions for those acts; let

me observe unto your lordships, and so leave this point, that albeit this petition, whereon this act

of 28 Ed. I., was grounded, be perished; yet hath it pleased God, that the very frame and context

of the act itself, as it is drawn up, and entered upon the Statute-roll, and printed in our book, doth

manifestly import, that this saving came in by the king's answer, and was not in the original

petition of the Lords and Commons; for it cometh in at the end of the act after the words (le roy ie

veut) which commonly are the words of the royal assent to an Act of Parliament. And though

they be mixed and followed with other words, as though the king's counsel, and the rest who were

present at the making of this ordinance, did intend the same saving; yet is not that conclusive, so

long as by the form of those times, the king's answer working upon the materials of the petition,

might be conceived by some to make the law effectual, though varying from the frame of the petition.

The next reason which the Commons have commanded me to use, for which they still desire

to be spared from adding this clause to their petition, is this: This offensive law of 28 E. I., which

confirmed Magna Charta, with a saving, rested not long in peace, for it gave not that satisfaction to

the lords or people, as was requisite they should have in a case so nearly concerning them: and

therefore about 33 or 34 of the same king's reign, a latter Act of Parliament was made, whereby it

was enacted, that all men should have their laws, and liberties, and free customs, as largely and

wholly as they had used to have at any time when they had them best; and if any statutes had

been made, or any customs brought in to the contrary, that all such statutes and customs should

be void.

This was the first law which I call now to mind, that restored Magna Charta to the original

purity wherein it was first moulded, aibeit it hath since been confirmed above twenty times more

by several Acts of Parliament, in the reigns of divers most just and gracious kings, who were most

apprehensive of their rights, and jealous of their honours, and always without savings; so as if

between 22 and 34 Edw. I., Magna Charta stood blemished with many savings of the king's rights

or seigniory, which might be conceived to be above the law; that stain and blemish was long since

taken away, and cleared by those many absolute declarations and confirmations. of that excellent

law which followed in after ages, and so it standeth at this day purged and. exempted now from

any such saving whatsoever.

I beseech your lordships therefore to observe the circumstance of time, wherein we offer

this petition to be presented to your lordships, and by us unto his Majesty: Do we offer it when

Magna Charta stands clogged with savings ? No, my lords, but at this day, when latter and

better confirmations have vindicated and set free that law from all exceptions; and shall we now

annex another and worse saving to it, by an unnecessary clause in that petition, which we expect

should have the fruits and effects of a law? Shall we ourselves relinquish or adulterate that, which

cost our ancestors such care and trouble to purchase and refine? ~No, my lords, but as we should

hold ourselves unhappy, if we should not amend the wretched estate of the poor subject, so let us

hold it a wickedness to impair it.

Whereas it was further urged by your lordships, That to insert this clause into our petition,

would be no more than to do that again at your lordships' motion and request, which we bad

formerly done by the mouth of our Speaker; and that there is no cause why we should recede from

that which so solemnly we have professed: To this I answer and confess, it was then in our hearts,

and it is now, and shall be ever, not to encroach on his Majesty's sovereign power. But I beseech

your lordships to observe the different occasion and reference of that protestation, and of

this clause.

That was a general answer to a general message, which we received from his Majesty

warning us not to encroach upon his prerogative; to which, like dutiful and loving subjects, we

answered at full, according to the integrity of our own hearts; nor was there any danger in making

such an answer to such a message, nor could we answer more truly or more properly: but did that

answer extend to acknowledge "a sovereign power" in the king, above the laws and statutes mentioned

in our petition, or control the liberties of the subjects, therein declared and demanded?

No, my lords, it hath no reference to any such particulars; and the same words which in some

cases may be fit to be used, and were unmannerly to be omitted, cannot in other cases be spoken,

but with impertinency at the least, if not with danger. I have formerly opened my reasons,

proving the danger of this clause, and am commanded to illustrate the impertinency of adding it to

the petition, by a familiar case, which was put in our House by a learned gentleman, and of my own

robe; the case is this, two manors or lordships lie adjoining together, and perchance intermixed,

so as there is some difficulty to discern the true bounds of either; as it may be touching the

confines where the liberty of the subject and the prerogative of the crown do border each upon

the other; to the one of the manors the king hath clear right, and is in actual possession of it, but

the other is the subject's. The king being misinformed, that the subject hath intruded upon his

majesty's manor, asketh his subject, whether he doth enter upon his majesty's manor, or pretendeth

any title to it, or any part of it. The subject being now justly occasioned, maketh answer truly to

the king, that he hath not intruded, nor will intrude upon his Majesty's manor, nor doth make any

claim or title to it, or any part of it. This answer is proper and fair; nay, it were unmannerly

and ill done of the subject not to answer upon this occasion. Afterwards the king, upon colour of

some double or single matter of record, seizeth into his highness's hands, upon a pretended title,

the subject's manor: the subject then exhibiteth his Petition of Right to his Majesty, to retain

restitution of his own manor, and therein layeth down title to his own manor only: Were it not

improper and absurd, in this case for him to tell the king, that he did not intend to make any claim

or title to his Majesty's manor, which is not questioned? Doubtless it were. This case, rightly

applied, will fit our purpose well, and notably explain the nature of our petition.

Why should we speak of leaving entire the king's "sovereign power," whereon we encroach

not, while we only seek to recover our own liberties and privileges, which have been seized upon

by some of the king's ministers ? If our petition did trench actually upon his Majesty's prerogative,

would our saying, that we intended it not, make the thing otherwise than the truth?

My lords, there needeth no protestation or declaration to the contrary of that which we

have not done; and to put in such a clause, cannot argue less than a fear in us, as if we had

invaded it: which we hold sacred, and are assured, that we have not touched either in our words or

in our intentions. And touching your lordships' observation upon the word (leave), if it be not a

proper word to give any new thing to the king, sure we are, it is a word dangerous in another

sense; for it may amount, without all question, to acknowledge an old right of "sovereign power"

.in his Majesty, above those laws and statutes whereon only our liberties are founded; a doctrine

which we most humbly crave your lordships' leave freely to protest against. And for your

lordships' proffering, that some saving should be requisite for preservation of his Majesty's

"sovereign power" in respect our petition runneth in larger words than our laws and statutes

whereon we ground it; what is this but a clear confession by your lordships, that this clause was

intended by you to be that saving ? For other saving than this we find not tendered by you; and

if it be such a saving, how can it stand with your lordships' other arguments, that it should be of no

other effect than our former expression to his Majesty by the mouth of our Speaker? But I will

not insist upon collections of this kind; I will only shew you the reasons of the Commons, why

this petition needeth no such saving, albeit the words of these statutes be exceeded in the declaratory

part of our petition: those things that are within the equity and true meaning of a statute,

are as good laws as those which are contained in the express letter, and therefore the statutes of

the 42 Edw. III., 36 Hen. III., Rot. Par. n. 12, and other the statutes made in this. time of King

Edw. III., for the explanation of Magna Charta, which hath been so often vouched in this

Parliament, though they differ in words from Magna Charta, had so saving annexed to any of them,

because they enacted more than was contained in effect in that good law, under the words, "per

legale judicium parium suorum, aut per legem terrae;" which by these latter laws are expounded to

import, that none should be put to answer without presentment, or matter of record, or by due

process, or writ original: and if otherwise, it should be void, and holden for error.

It hath not been yet shewn unto us from your lordships, that we have in any of our

expressions or applications strained or misapplied any of the laws or statutes whereon

we do insist; and we are very confident and well assured, that no such mistaking can be

assigned in any point of our petition now under question: If therefore it do not exceed the

true sense and construction of Magna Charta in the subsequent laws of explanation, whereon it is

grounded; what reason is there to add a saving to this petition more than to those laws; since we

desire to transmit the fruits of these our labours to posterity, not only for the justification of ourselves,

in right of our present and their future liberties, but also for a brave expression and

perpetual testimony of that grace and justice, which we assure ourselves we shall receive in his

Majesty's speedy and clear answer? This is the thing we seek for, and this is the thing we hoped

for, and this is the thing only will settle such an unity and confidence betwixt his Majesty and us,

and raise such a cheerfulness in the hearts of all his loving subjects, as will make us proceed

unanimously, and with all expedition, to supply him for his great occasions in such measure, and in

such way, as may make him safe at home, and feared abroad.

The House of Lords at last agreed with the Commons in omnibus, and shortly

after King Charles unwillingly gave his assent to this Petition of Right, and having

received it the Parliament and whole country became a little more satisfied, and the

dark cloud hovering over England for a short time disappeared.

In October, 1625, Mr. Glanville acted as Secretary-at-War to the Cadiz expedition,

although by a letter of his, still in existence, he appeared to have much objected to this

appointment, and he gave his reasons for doing so. On 7th March, 1626, he returned

from the seat of war in company with Lord Wimbledon.

In 1630 Glanville was chosen Lent Reader of his House, and on the 20th May,

1637, advanced to the rank of Serjeant-at-Law. [fn 122] In 1635 Glainville and Mr. Rolles were

ordered by the Lords, sitting in the celebrated Star Chamber, to end the difference (if

they were able) between Lord Poulett and the Reverend Richard Gove.

Glanville also held the office of Notary and Prothonotary to the Court of Chancery

with the fee of £100 per annum, payable out of the Hanaper, in trust for Lady

Thomasine Carew and John Howston his Majesty's servant, in reversion with John

Glanville.

In the year 1639 Serjeant Glanville acted in the capacity of a Judge and the

following extracts from a letter will shew the business he was then upon: [fn 123]

Aug. 26, 1639, Bishop Skinner of Bristol, writing to Archbishop Laud, says, "I should not

have been troublesome now to you had not Davis's arraignment at Bristol occasioned it. He was

arraigned on Wednesday the 21st inst., and returned by the jury 'Not Guilty.' But why not

guilty? when the evidence was so pregnant and the witnesses so constant and confident. I think

the Judge himself is yet unsatisfied. The Tuesday night before I had free conference with

Serjeant Glanville, who sat as Judge, about the whole case, and my desire to him was that a

matter of this high nature might not be slighted, nor slumbered over, but carried at least with

severity so as metus ad omnes, at which time he, Glanville, told me that he had advised upon the case

with the Lord Keeper, Judge Croke, and the Attorney-General, whose opinions he repeated, and

moreover said that he had been with you also. The truth is, both in his charge and arraignment,

and even after Davis was quit by the jury, the Judge did his part copiously, gravely, and with

semblance of great severity. The Judge (Glanville) took his cue to know of the prisoner what he

thought of Bishops, hiasanswer was that he thought their calling to be the ordinance of God, and

that they were appointed by Christ for the government of his church, and at last, upon the 'Not

Guilty,' lie kneeled down and prayed for the King, Archbishops, and Bishops, and for all the

Magistrates, etc. My conceit upon the whole matter is this, that the whole carriage of the

business was a mere scene, wherein the Judge acted his part cunningly, the jury plausibly populo

ut placerent, and the prisoner craftily, that he might no longer resemble Davis qui pertubat

omnia."

Another extract from a letter in the same collection may be of interest:-

April 13, from Burdrop, 1640. Sir William Calley, writing to Richard Harvey, says, "I

pray speak to Mr Long that in future my letters to him may be opened though he be from home

and the inclosures delivered to you. Mr. Serjeant Glanville told me that he had bought Highway

for £4700 and shewed me the articles. I marvel that you never wrote to me of the arrival of Sir

Peter Wyche, considering our former acquaintance with him and with the means which were used

for his first employment in Turkey."

In the Parliament summoned to meet at Westminster, 13th April, 1640, in the

16 Charles I., between eight and nine in the morning, the Earl Marshal of England,

Lord Steward of his Majesty's Honourable Household, came into the outward room of

the Commons' House, accompanied with the Treasurer of the Household, Mr. Secretary

Windebank, and others, where the Clerk of the Crown, attended by the Cryer of

Chancery, called over the names of all such knights, citizens, burgesses, and barons of

the Cinque Ports as were then returned; and the said Lord Steward having sworn about

forty, did make his deputation under his hand and seal, which was read, and which did

nominate many of the Privy Council and other members of the House of Commons,

thereby authorising them or any one or more of them to administer the oaths of

supremacy and allegiance to all the members of the said House during that Parliament;

and so departed to wait upon the King.

About twelve o'clock his Majesty, accompanied by all his nobles and other

principal officers in great solemnity, rode in state from Whitehall to Westminster Abbey,

and there heard a sermon preached by the Bishop of Ely, and from thence they went to

the House of Lords. When the King was seated on his throne, and the Prince seated on

his left hand, and all the Lords appearing in their robes, the Commons were called into

the House of Peers, when hip Majesty made this short speech,-

"MY LORDS AND GENTLEMAN,

"There was never a King that had more great and. weighty cause to call his people

together than myself. I will not trouble you with the particulars; I have informed my Lord

Keeper, and commanded him to speak and desire your attention."

Then Sir John Finch, Lord Keeper, in obedience to his Majesty's commands, rose

up and delivered his speech to the assembled Lords and Commons, which being finished,

King Charles addressed the Lords again, and when he had ended the Lord Keeper spoke

to the Commons thus:-

"GENTLEMEN,

"You. of the House of Commons, His Majesty's pleasure is that you do now repair to

your own House, there to make choice of your Speaker, whom his Majesty will expect to be

presented to him on Wednesday next at two of the clock in the afternoon."

The Commons then returned to their own House, and being seated, Mr. Treasurer

put them in mind of the King's command for choosing a Speaker, not one of the King's

own appointment, but freely among themselves, and then he nominated Mr. Serjeant

Glanville. Mr. Serjeant Glanville then stood up and acquainted the House that he

accounted it an honour to be named, but to be accepted a disadvantage to the House, and

endeavoured to excuse himself from the occasion of the summons, which was a matter of

weight. His excuse more raised the acclamations, To the Chair! To the Chair! and so at

length, between Mr. Treasurer Vane and Mr. Secretary Windebank, he was brought to

the chair, where again he excused himself, and afterwards appealed to the royal judgment

of his Majesty.

Upon Wednesday, the 15th of April, his Majesty being seated on his throne, Mr.

Serjeant Glanville was called in and was presented by the House of Commons as their

Speaker, and he approaching the bar spake as follows:-

"May it please your Majesty:

"The knights, citizens, and burgesses of your Commons' House of Parliament, in conformity

to most ancient and most constant usage (the best guide in great solemnities), according to their

well-known privileges (a sure warrant for their proceedings), and in obedience to your Majesty's

most gracious counsel and command (a duty well becoming royal subjects), have met together in their

House and chosen a Speaker, one of themselves, to be the mouth indeed your servant of all the

rest, to steer watchfully and prudently in all their weighty consultations and debates, to collect

faithfully and readily the genuine sense of a numerous assembly, to propound the same seasonably,

and. in apt questions of their final resolutions, and so represent them and their conclusions, their

declarations and petitions, upon all urgent occasions, with truth, with right, with life, and with

lustre, and with full advantage to your most excellent Majesty. With what judgment, what temper,

what spirit, what elocution ought he to be endowed and qualified, that, with any hope of good success,

should undertake such employment? Your Majesty in your great wisdom is best able to discern and

judge, both as it may relate to your own peculiar and most important affairs of State and Government,

and as it must relate to the proper business of your House of Commons, which was never

final nor mean, and is like at this time to be exceeding weighty. Had your House of Commons

been as happy in their choice (as they were regular, well warranted, and dutiful) of myself who

stand elected yet to be their Speaker, and am now presented by them to your Majesty for your

gracious and royal approbation, I should not have needed to become troublesome to your Majesty

in this suit, for my releasement and discharge, which now, in duty to your Majesty and care for

the good prosperity and success of your affairs, I hold myself obliged to make. My imperfections

and disabilities are best known to myself, to your Majesty I suppose not altogether unknown,

before whom, in the Court of my practice and profession, I have divers times had the honour

and favour to appear and bear a part as an ordinary pleader.

"It is a learned age wherein we live under your Majesty's most peaceful and flourishing

government, and your House of Commons (as it is now composed) is not the only representative

body, but the abstracted quintessence of the whole commonalty of this your noble realm of

England; there be very many amongst them, much fitter for this place than I am, few or none, in

my opinion, so unfit as myself. I moat humbly beseech your Majesty, as you are the father of the

Commonwealth and head of. the whole Parliament, to whom the care of all our welfare chiefly appertains,

have respect to your own ends, have regard to your House of Commons, have compassion

upon me the most unworthy member of that body, ready to faint with fears before the burthen

light upon me.

"In the fulness therefore of your kingly power, your piety and your goodness, be

graciously pleased to command your House of Commons once more to meet together to consult and

deliberate better, about their choice of a meet Speaker, till they can agree of some such person as

may be worthy of their choosing, and of your Majesty's acceptance."

The Lord Keeper, after receiving directions from his Majesty, replied .as follows:

"His Majesty, with a gracious ear, a princely attention, hath listened to your humble and

modest excuse, full of flowers of wit, of flowers of eloquence, and flowers of judgment.

"Many reasons from yourself he hath taken to approve and agree to the choice and

election, made by the House of Commons. He finds none from anything that you have said, to

dissent or disagree from it: you have set forth your inabilities with so much ability, you have so

well deciphered and delineated the parts, duties, and offices of a good Speaker, which is to collect

the sense of the House judiciously, to render it with fidelity, to sum it up with dexterity, and to

mould it up into fit and apt questions for resolutions, and those, as occasion shall serve, to present

with vigour, advantage, and humility to his Majesty, he doubts not but that you, who are so perfect

in the theory, will with great ease perform the practick part, and with no less commendation.

"His Majesty hath taken notice, and well remembers, your often waiting on him in private

causes, wherein you have always so carried yourself, and won so much good opinion from his

Majesty, as he doubteth not but that now when you are called forth to serve him and the

publick, your affections and the powers of your soul will be set on work with more zeal and more

alacrity. It's that for which the philosophers call a man happy, when men that have ability and

goodness, to meet with an object fit to bring into act, and such at this time is your good fortune,

an occasion being ministered unto you, to shew your ability and goodness, and your fidelity to his

Majesty's service, to shew the candor and clearness of your heart towards those of the House of

Commons; in all which his Majesty nothing doubteth, but you will so discharge yourself, as he

may to his former favours, find occasion and reason to add more unto you, that the House of

Commons may rejoice in this election of theirs, and that the whole kingdom, by your good, clear,

and candid service, may receive fruits that may be comfortable unto all.

"His Majesty therefore doth approve and confirm the choice of the House of Commons,

and ratifies you for the Speaker."

Speaker Glanville then rose, and addressing the King, said -

"Most gracious Sovereign, - My profession hath taught me, that from the highest judge

there lies no writ of error, no appeal. What then remains, but that I first beseech Almighty God,

the author and finisher of all good works, to enable me to discharge honestly and effectually, so

great a task, so great a trust; and in the next place, humbly to acknowledge your Majesty's favour.

Some enemies I might fear, the common enemy of such services, expectation and jealousy; I am

unworthy of the former, and I contemn the latter; hence the touchstone of truth shall teach the

babbling world I am, and will be found, an equal freeman, zealous to serve my sovereign, zealous

to serve my country.

"A king's prerogative is as needful as great; without which he would want that majesty

which ought to be inseparable from his crown; nor can any danger result thereby to the subjects'

liberties, so long aas both admit the temperament of law and justice, especially under such a prince,

who, to your immortal honour, hath published this to the whole world as your maxim, that the

people's liberties strengthen the king's prerogative, and the king's prerogative is to defend the

people's liberties; apples of gold in pictures of silver.

"Touching justice, there is not a more certain sign of an upright Judge, than by his

patience to be well informed before sentence is given; and I may boldly say, that all the judges in

the kingdom may take example of your Majesty, and learn their duties by your practice: myself

have often been a witness thereof, to my no little admiration.

"From your patience, give me leave to press to your righteous judgment, and exemplify

it, but in one instance. When your lords and people, in your last Parliament, presented your

Majesty a petition concerning their rights and liberties, the petition being of no small weight,

your Majesty, after mature deliberation, in a few but most effectual words (soit droit fait comme

est desire) made such an answer, as shall renown you for just judgment to all posterity.

"Were this nation never so valiant and wealthy, if unity be not among us; what good will

riches do us, or your Majesty, but enrich the conqueror? He that commands all hearts by love, he

only commands assuredly; greatness without goodness can at best but command bodies.

"It shall therefore be my hearty prayer, that such a knot of love may be knit betwixt the

head and the members, that, like Gordian's, it never be loosed; that all Jesuited foreign states,

who look asquint upon our Hierusalem, may see themselves defeated of all the subtle plots and

combinations of all their wicked hopes and expectations, to render us, if their mischief might take

effect a people inconsiderable at home and contemptible abroad. Religion hath taught us 'si deus

nobiscum quis contra nos?' and experience I trust will teach us 'si sumus insuparabiles.' It was

found, and I hope it will ever be the term of the House of Commons, that the King and the

people's good cannot be severed, and cursed be every one who goes about to destroy them."

[fn 124]